Historical Textual Records

Before you read the old records

Jacinta is a researcher who advocates for self-love, justice, and reconciliation, emphasising First Nations family rights to their archives, historical Textual Records. She calls for greater investment in culturally informed and critically examined ancestry research. Jacinta proposes that critical and trauma-informed genealogy research is a therapeutic, empowering practice and a crucial element for truth-telling and reconciliation. She contends that we are all interconnected and must collectively bring meaningful change for not only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families but for all our health and wellbeing.

Genealogy is one of humanity's oldest sciences, driving historical inquiry by tracing familial origins. Critical family history research can shift individual and collective consciousness and drive meaningful change by promoting self-awareness, awakened historical understandings, and compassion for others. This is especially important in a world now seemingly filled with violence and indifference.

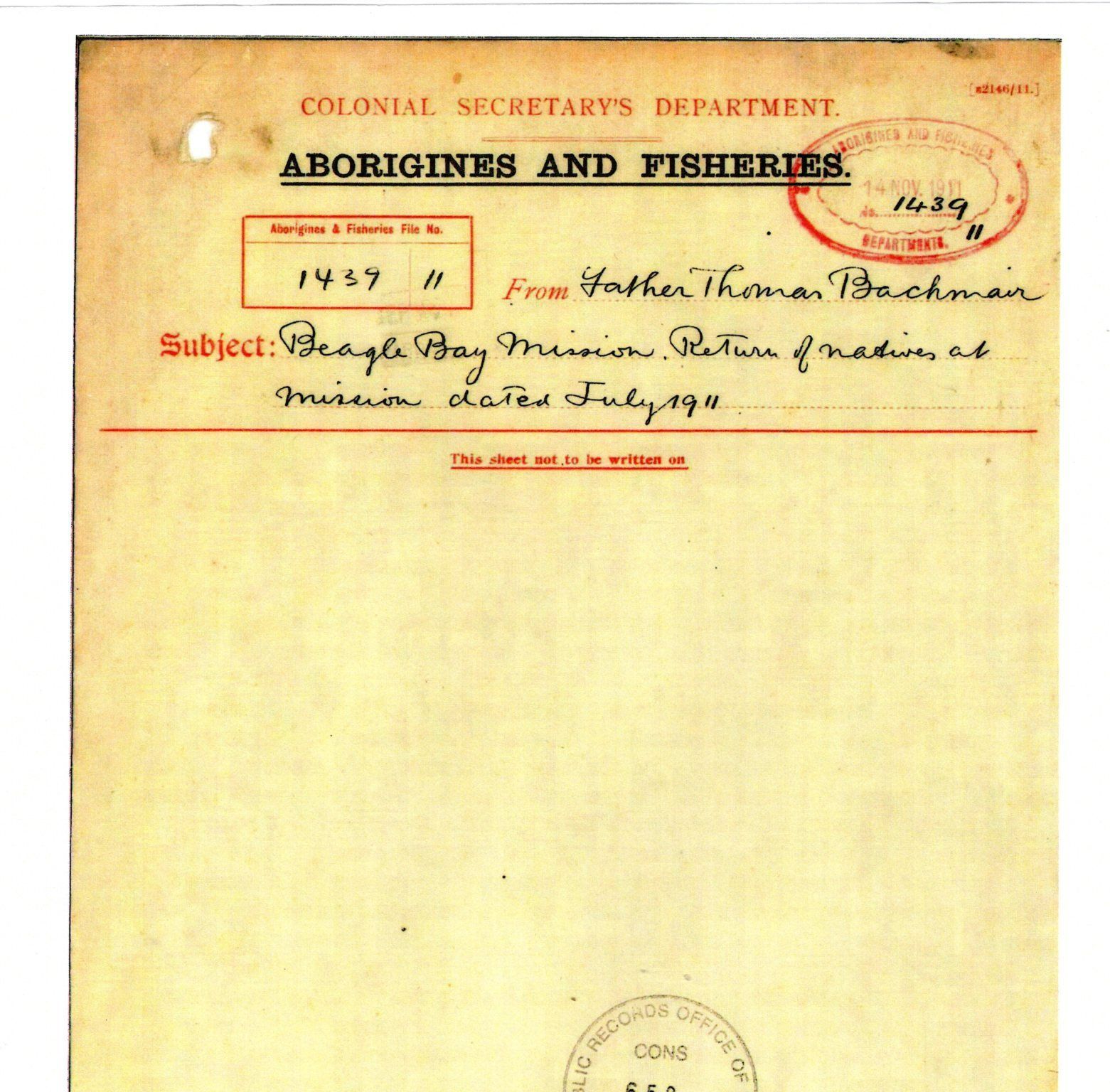

Connection with and access to Country, kinship, and cultural knowledge are essential for the health and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Since the colonisation of Australia, these connections have been the target of intrusive research and violent attack through government policy and settler activity and recorded extensively within textual records. Ironically, these violent records now serve as crucial sources of information for all Australians. They have become powerful tools for healing, empowerment, and truth-telling as was recently asserted by the Victorian Yoorrook Justice Commission.

Jacinta's PhD thesis narrates seven generations of spirit and colonisation from her family's perspective in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Through her storytelling, she highlights the role of the archives and the support of archivists in enabling her family’s remembrance of self. Jacinta calls for more leadership and cooperation by archive-holding institutions to improve access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. She emphasises that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family narratives are integral to our whole nation's identity, and our nation's ability to locate, name, and reconcile our Indigenous and non-Indigenous family relations as central to our understanding of our past and ability to heal and prosper together in the future.

Please Take Care of Yourself.

All records shared on this website are either publicly available or are carefully considered family historical documents approved by the family to be shared. These documents are evidence of violent treatment of Aboriginal families in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The way Aboriginal people are described in these old records, is highly offensive. These documents hold the painful memories and stories of those deceased and their descendants. Be kind to yourself when reading this material, and be kind to others.

If you are Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander and need emotional support, please contact 13Yarn.

Travelling Inspector of Police James Isdell

In 1907, the year of Jacinta's great-grandmother's birth, the Aborigines Department recruited Travelling Inspector of Police James Isdell. Isdell was a former independent liberal parliamentarian for the Pilbara region. Prior to his time in politics, Isdell was a farmer and pastoralist at Karratha station near Roebourne, Lake Edah Cattle Station near Broome, and an owner of Croyden Station. Between 1888 and 1903 he was a gold prospector and storekeeper in the Pilbara and in 1904 a mine manager at Nullagine. The year Mabel was born, in 1907, Isdell became Travelling Inspector under the direct leadership of the Aborigines Department. Having worked in politics, farming, and mining, he was under no illusions that his role was to protect the rights of pastoralists and miners through the management and organisation of the Aboriginal people in his charge. Isdell was engaged as Inspector for the Marble Bar and Kimberley districts until 1909.

While employed in policing, he received an annual salary of £325 which included a £75 annual forage allowance and in 1911 this also included a £55 annual district allowance, in accordance with section 71 of the Police Service Regulations Act. This extra allowance was designed to attract and retain police in the remote Kimberley region.

James Isdell was a passionate, loyal, and hard-working servant to the British establishment. He very rarely took leave from work, only doing so when he was gravely ill. He was an experienced bushman, very proud of his work ethic and achievements. He held strong beliefs regarding the ‘native’ population he was employed to oversee. He believed in his role to protect the Aboriginal population; however, his ideas of what this ‘protection’ was to look like were influenced deeply by European Darwinist theories of race superiority. He believed Aboriginal people were an inferior and immoral race that required his direction and management.

"I would not hesitate for one moment to separate any half-caste from its aboriginal mother, no matter how frantic her momentary grief might be at the time. They soon forget their offspring."

These are the words of Travelling Police Inspector and Protector, James Isdell, written for the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, Charles Frederick Gale, published in the Department of Aborigines and Fisheries annual report for the financial year ending 30th June 1909.

Isdell was concerned primarily with two issues in the Kimberley district: the high prevalence of cattle killing in the region (families feeing themselves on Country) and the growing Aboriginal ‘half-caste’ population (the children to white pastoralist and police). Isdell was a fierce advocate for the removal of these half-caste children and the segregation of Aboriginal people onto reserves.

In his role as Travelling Inspector in the Kimberley, he knew very well the issues of widespread pastoralist leases occupying vast lands, by effect was leading to the displacement of thousands of Aboriginal people and disruption to their abilities to feed themselves.

In 1909 he strongly argued for an allotment of land in the Kimberley to be set aside and stocked with enough cattle to provide a training ground for Aboriginal station workers and to feed local Aboriginal families. On 16th August 1909, Isdell wrote to the Honourable Chief Secretary of Colonial Affairs to express these concerns. Isdell’s communications with the Department were instrumental in the establishment of the Moola Bulla Aboriginal Pastoral Settlement in 1910. In his retirement he boasted of his part in its establishment and its tremendous success in curbing the cycle of incarceration of Aboriginal men and boys and dramatically reducing the instances of cattle killing in the north. In 1910, he became Protector of Aborigines at Turkey Creek and was in this role till 1915.

- Fisheries Department [2], Department of Aborigines and Fisheries, and Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority. “Photograph of ‘Travelling Aboriginal Protector Isdell’,” Item, December 31, 1920. AU WA S4879- cons7620 010. SROWA.

- Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “J. Isdell. Diary 1909,” Item, 1909. AU WA S1644- cons652 1909/0213. SROWA. Transcribed Document.

- Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “J. Isdell. Reports Difficulty in Obtaining Number and Locality of Half Castes,” Item, 1909. AU WA S1644- cons652 1909/0488. SROWA.

- Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “J. Isdell. Kimberley Downs Station - Employment of Natives - Complaint by Manager Re Interference of Police,” Item, 1909. AU WA S1644- cons652 1909/0429. SROWA.

- Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “J. Isdell. Prohibited Areas at Derby, Fitzroy Crossing, Halls Creek and 3 Miles Wyndham Recommended by Him. States He Had Received No Notification of Declaration,” Item, 1909. AU WA S1644- cons652 1909/1296. SROWA.

- Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “J. Isdell. Diary - 1910,” Item, December 31, 1910. AU WA S1644- cons652 1910/0383. SROWA.

- Aborigines Department. “James Isdell. Annual Report, 12 Months Ended 30 June 1911,” July 1911. AU WA Cons 652, Item 1911/0987. SROWA.

- Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “I. Isdell. Cattle Killing - Report Re Prevalence of in Kimberley District,” Item, August 16, 1909. AU WA S1644- cons652 1909/0989. SROWA.

- Colonial Secretary’s Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. “J. Isdell. Half Castes: Re 2 Half Caste Children at Turkey Creek (Brought from Ord River by Const. Nicholson in May 1911),” Item, September 26, 1911. AU WA S1644- cons652 1911/1216. SROWA.

- Chief Secretary’s Department, and Colonial Secretary’s Office. “Aborigines and Fisheries Department. James Isdell - Personal File,” Item, October 13, 1919. AU WA S675- cons752 1911/2892. SROWA.

- Western Australia, and Walter Edmund Roth. Royal Commission on the Conditions of the Natives Report. Government Printer, 1905. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-61348422.

- Henry Doyle Moseley, “1935 Western Australia Report of the Royal Commissioner Appointed to Investigate, Report, and Advise upon Matters in Relation to the Condition and Treatment of Aborigines,” 1934.https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52802043/view?partId=nla.obj-95327045

- “Aboriginal Welfare : Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities Held at Canberra, 21st to 23rd April, 1937.” https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52771316.

- 1927 Western Australian Royal Commission Inquiry into Alleged Killing and Burning of Bodies.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-352760692

Nation-wide Sources

- State Library of NSW. First Fleet Collection. This collection includes journals, letters, drawings, maps and charts created by those who travelled with the First Fleet to Australia in 1788.

- National Archives of Australia. The Immigration Restriction Act 1901.

- National Museum Australia. White Australia policy.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIASTS), To Remove and Protect, Legislations, Protection Reports and various Archives.

- National Library of Australia, First Australians Family History.

- Trove, historical documents, newspaper articles, government documents, mission documents, photos, etc..

- Early experiences in Australasia : primary sources and personal narratives, 1788-1901: https://search-alexanderstreet-com.ap1.proxy.openathens.net/eenz

- Public Records Office Victoria, Aboriginal Victorians (1830s – 1970s).

- State Records Office of Western Australia, Search results "Aboriginal".

- Aboriginal History WA, General researcher.

- Queensland State Archives, Search results "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander".

- State Records of South Australia, Search results "Aboriginal".

- State Archives Collection - Museums of History NSW, First Nations Community Access to Archives.

- State Records NSW, Search Results "Aboriginal".

- Libraries Tasmania, Tasmanian Aboriginal History, Collections and Access.

- Northern Territory Archives, Search "Aboriginal".

- There is a website created by the Aboriginal political activist Gary Foley that provides a range of primary sources:http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/indexb.html

- There is a website devoted to the subject of massacres. Each event provides direct online access to newspaper articles documenting the violence. See: https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/introduction.php

- The Healing Foundation has published and online map of Missions and Reserves around Australia. See: Map of Stolen Generations Institutions

- For a website about Aboriginal people's lived experiences in Sydney, see: http://historyofaboriginalsydney.edu.au/

- For a website about an Aboriginal strike in the Pilbara, see: https://www.pilbarastrike.org/

- A collection of primary source documents about colonial frontiers in Australia, North America and Africa see: https://www.frontierlife.amdigital.co.uk/